75 years after Jackie Robinson’s MLB debut, hardball’s racial gap is widening

When Lashandra Clark Callahan worked as a greeter at Truist Park, she occasionally brought her son, Jahliel, with her to the games to cheer the Atlanta Braves.

He loved it.

But as close as he was to the game, access and expenses made it almost impossible for him to actually play the game.

“Living in Atlanta, there were not many opportunities for him to play baseball,” Callahan said. “I couldn’t find a team for him. Everybody was playing basketball and football, but I didn’t want him to be that typical Black boy who was only into football and basketball.”

Credit: Lashandra Clark Callahan

Jahliel, now a 12-year-old, eventually latched on to C.J. Stewart’s L.E.A.D., an Atlanta-based mentoring program that seeks to help low-income Black youths through baseball.

“He wasn’t very good when he started,” Callahan said of her son. “But that is alright, because he is getting better and they are teaching him fundamentals of being a Black man.”

As America on Friday marks the 75th anniversary of Jackie Robinson breaking Major League Baseball’s color barrier, the game of baseball is still struggling to attract Black ballplayers.

And Stewart, who has trained eventual major leaguers like Jason Heyward and Dexter Fowler, is feeling the pinch.

He said the rising cost of gas has forced him to slash his program from 50 kids to 15.

Stewart’s program provides transportation from public middle schools to playing fields and drops each child at home after the game, along with afterschool meals and even haircuts. He says L.E.A.D. couldn’t afford to pick up all the kids anymore and parents couldn’t afford to get them there.

“They are very frustrated, but you can’t have fun without funding,” Stewart said.

Friday night, when the Braves hit the field against the San Diego Padres, every player will be wearing Robinson’s number 42. But by all accounts, the broader numbers are dire.

Even with shining stars like Aaron Judge of the New York Yankees, Mookie Betts of the Los Angeles Dodgers and Tim Anderson of the Chicago White Sox, just 7.2% of the players on MLB opening day rosters this season were Black, down from the 7.6% last year, according to the Society of American Baseball Research.

That percentage has fallen consistently since MLB’s all-time high of 18.7% in 1981, in a country where Black people currently make up 13.4% of the population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Credit: Ross D. Franklin

Even before Jackie Robinson landed with the Dodgers in 1947, baseball was once a staple of Black culture, largely because of the popularity of the Negro Leagues and players like Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson.

Some experts and studies suggest that the decline of Black baseball players is because fame and fortune come slower in baseball. While NFL and NBA stars can come right out of college to earn big bucks, it can take years in baseball’s minor leagues to make it to the majors.

There is also the issue of affordability. The best youth players join year-round travel teams and are afforded quality equipment and private coaches. Travel costs alone make it impossible for kids from underserved communities to participate, making it harder to get exposure, scholarships and a shot at getting drafted.

It is something that Stewart knows firsthand.

Born when his mother was 16 and raised in Atlanta public housing, Stewart learned the game from his grandfather, who watched Chicago Cubs and Braves games every day on cable. Stewart became a star at Atlanta’s Westlake High School and was drafted by the Cubs in 1994. He instead went to college and was drafted again by the Cubs in 1996.

He lasted two years in pro ball, before quitting to coach and mentor.

“If you are a Black boy and don’t want to submit to white culture, the last thing you wanna do is play baseball. I struggled with that,” Stewart said.

In an effort to address the problem, MLB has created programs like Hank Aaron Invitational, where the best Black players in the country work with coaches and former players like Dave Winfield and Marquis Grissom for elite-level training. In 2021, the Atlanta Braves and MLB announced a $3 million partnership to increase access to youth baseball and softball programs in Georgia with a focus on promoting diversity. The Braves also have launched fellowships to boost diversity off the playing field.

Edwin Jackson, a former Braves pitcher who played for a major league-record 14 teams, said Black kids often are not afforded opportunities to play and struggle to find role models who look like them.

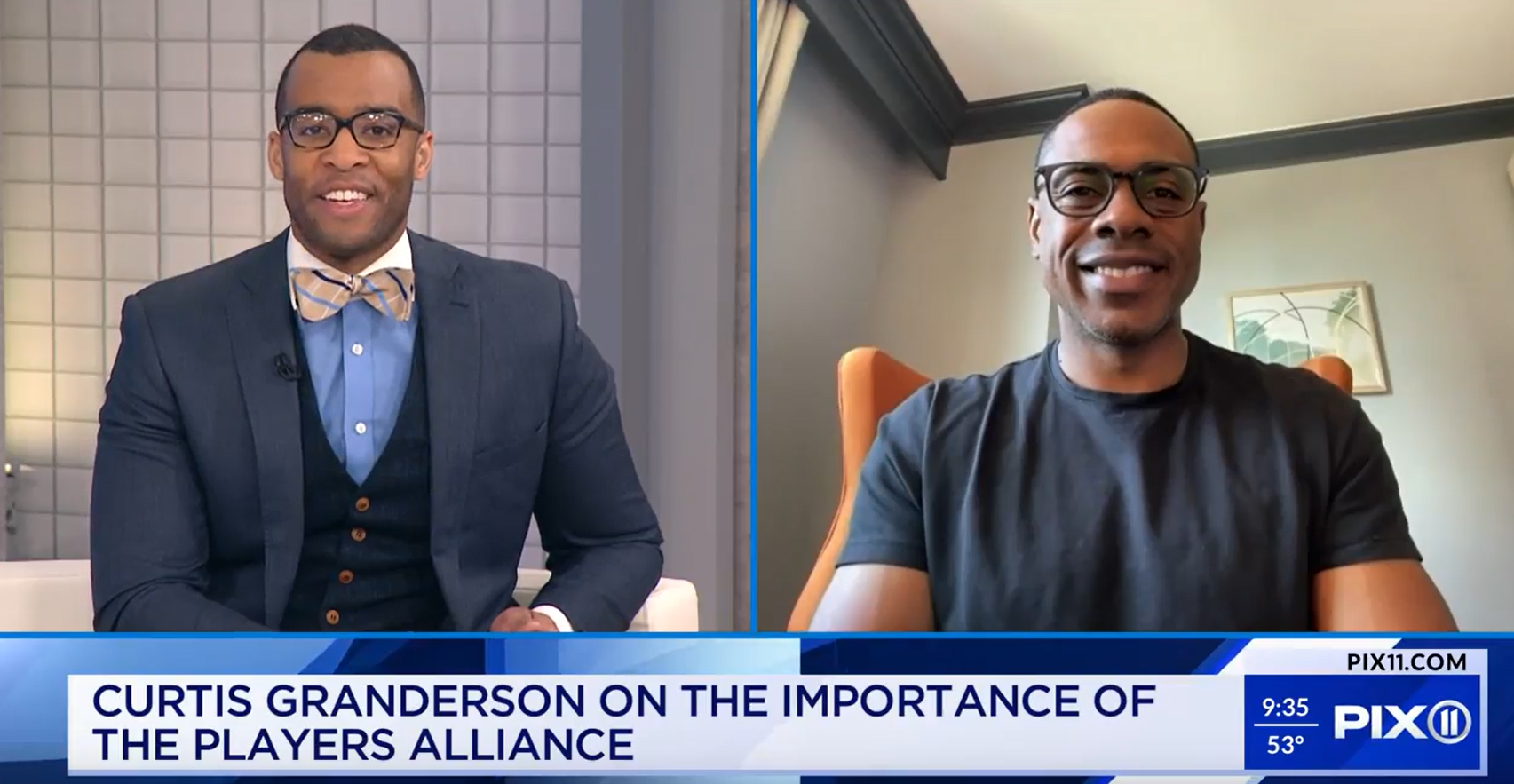

Credit: Players Alliance

“They don’t see us a lot on television, so we are not being marketed,” Jackson said. “We need Mookie and Tim Anderson on TV. You can’t be who you don’t see.”

This week, the Players’ Alliance, an organization of current and former ballplayers who are Black and co-founded by Jackson, donated $150,000 to L.E.A.D. It will fund 42 players — in honor of Robinson — for L.E.A.D.’s summer programs here in Atlanta.

“This is the most vital age group, where we can either lose them or pull them in,” Jackson said. “The only way to make a change is for us to do it personally. If we don’t go out and enlighten these kids, who else will?”

Stewart was surprised by the donation and rendered to tears. Proving that there is crying in baseball.

“This solves so many problems that we have,” Stewart said. “We now have a solution to make sure that we can actually protect boys from the idle time that can lead to crime, that can lead to death. We will be able to provide.”

Credit: Lashandra Clark Callahan

For Callahan and her son, Jahliel, it will be money well spent. Callahan is already planning to have him in the summer program.

“He never got into sports. He was always a kid who hid in his room reading a book or solving something on the computer,” Callahan said. “With baseball, he has grown to have more of a personality, without being afraid of being himself.”